Are you curious about the philosophical perspective on suicide? Wondering if suicide is morally wrong or if there are any philosophical quotes that shed light on this topic? Look no further! In this blog post, we dive deep into the world of philosophy and explore various perspectives on suicide. From ancient Greek views to stoicism, we’ll examine the philosophical underpinnings of this complex and sensitive subject. So, whether you’re seeking knowledge, contemplating life’s meaning, or simply looking for thought-provoking quotes, this article has got you covered. Let’s embark on this philosophical journey together and unravel the profound insights that philosophers have to offer on suicide.

Understanding the Philosophical Perspective on Suicide

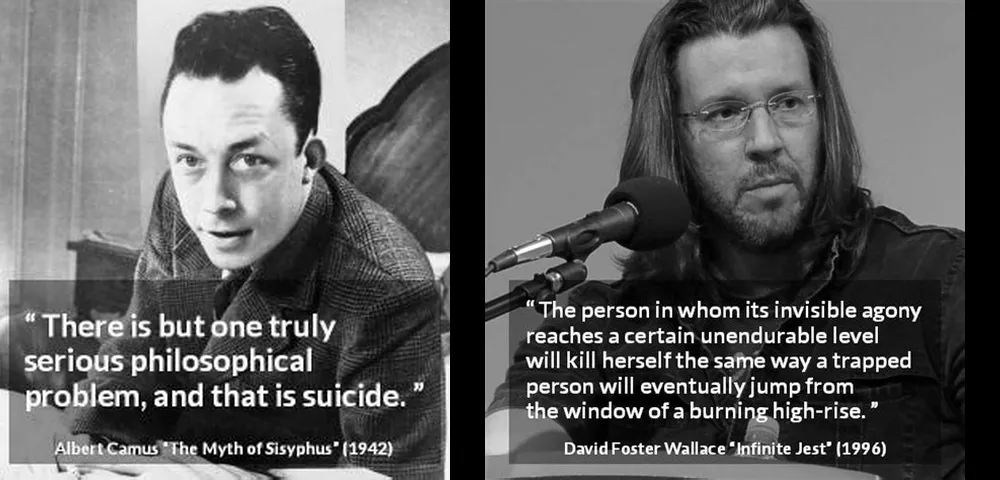

In the realm of philosophy, few subjects are as profound or as haunting as the contemplation of suicide. It is a topic that has perplexed thinkers since ancient times, leading them to question the very value of existence. Albert Camus, a luminary in existential philosophy, famously declared,

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.”

This stark proclamation sets the stage for a philosophical exploration of life’s worthiness in the face of suffering and despair. Let us delve into this existential conundrum through a tableau of philosophical insights.

| Philosopher | View on Suicide | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Albert Camus | Life’s inherent absurdity does not justify suicide; rather, it challenges us to seek meaning despite it. | “Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.” |

| Arthur Schopenhauer | While he viewed life as suffering, he believed that suicide was not a solution as it does not negate the will to live. | “They tell us that suicide is the greatest piece of cowardice… I ask you, is there anything more cowardly than to run away from life because you are not brave enough to endure it?” |

| David Hume | Argued against the immorality of suicide, considering it a release from unbearable pain or suffering. | “No man ever threw away life while it was worth keeping.” |

| Immanuel Kant | Strongly opposed suicide on moral grounds, citing the duty to preserve life as a categorical imperative. | “Self-murder… is abominable because no example of it can be given without contradicting and undermining… the humanity in one’s person.” |

These philosophical ruminations on suicide not only illuminate individual perspectives but also underscore the complexity of the subject. It is a decision that threads through the fabric of moral, existential, and metaphysical debates, challenging both the individual and society to confront the enigma of life’s meaning—or its perceived lack thereof.

In the tapestry of human experience, the act of contemplating suicide is, in itself, a philosophical exercise—a moment where one stands at the precipice of existential inquiry. As we weave through the philosophical discourse, we explore the intricate patterns of thought that have shaped our understanding of this most intimate decision.

As we continue, the following sections will further dissect the moral implications, the existential leaps of faith, and the historical perspectives on this profound issue. Each thread contributes to a larger understanding, as philosophy seeks not just to answer questions, but to question the answers we hold dear.

Is Suicide Morally Wrong?

In the labyrinth of moral philosophy, the question of whether suicide is morally wrong has perplexed thinkers for centuries. The essence of this debate is not simply a binary judgement of right or wrong. Instead, it calls for an exploration of the nuanced and complex tapestry of human ethics. Philosophers have grappled with this question, and many have arrived at the conclusion that suicide, in itself, is not inherently wrong. To characterize suicide as self-murder is to oversimplify and misinterpret the layers of human experience that lead to such an action.

One might argue that individuals hold sovereignty over their own lives, and as such, the decision to end one’s life is a deeply personal one. This perspective suggests that there is no universal duty to indefinitely prolong one’s existence, especially if it is marred by suffering that outweighs any potential good. The argument extends to the societal level as well, positing that while those who commit suicide may indeed deprive their community of potential contributions, this does not necessarily obligate them to endure personal torment for the greater good. Here, the philosophical discourse shifts from a question of duty to others to a question of duty to oneself.

Within this rich tapestry of thought, some voices have raised concerns about the wider implications of suicide. They ponder the ripple effects on families, friends, and society at large. Yet, the counterargument remains steadfast in the belief that moral agency and the autonomy of the individual take precedence. The philosophical inquiry into the morality of suicide thus becomes a delicate balance between the collective needs of society and the intrinsic rights of the individual.

As we navigate these intricate moral waters, it becomes evident that the question of suicide’s morality is far from a closed book. It continues to challenge our understanding of ethical principles and the profound complexities of the human condition. The discourse requires us to consider the depths of human suffering, the sanctity of life, and the boundaries of personal freedom. In the end, the philosophical stance on suicide opens up a space for continuous dialogue, rather than dictating a definitive moral verdict.

Philosophical Suicide: A Leap of Faith

Stoicism and Suicide

The ancient philosophy of Stoicism, cradled in the heart of Athens, teaches the pursuit of virtue and the mastery of emotions. Within this framework, the Stoics contemplated the complexities of life and death, including the act of ending one’s own life. In the Stoic view, suicide is considered neither a casual escape nor an inherent transgression, but rather a decision that should be measured against the tenets of wisdom and self-control.

It was Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher who endured the hardships of slavery before gaining his freedom, who declared, “There is only one way to happiness and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond the power of our will.” This profound statement encapsulates the Stoic belief that personal contentment lies in focusing on what we can control and detaching from what we cannot. When it comes to the matter of suicide, Stoicism posits that only a truly wise person—one who has achieved a deep understanding of life’s nature—can rightly discern the appropriate circumstances for such an act.

Stoicism acknowledges that life can present unbearable conditions, where suffering outweighs the potential for joy or virtue. In such extreme scenarios, a Stoic might consider suicide a rational choice. However, this is not a decision to be taken lightly or without profound introspection. The wise man, according to Stoic principles, would weigh this choice meticulously, ensuring it aligns with a life lived in harmony with nature and reason.

Thus, the Stoic perspective on suicide is intricately tied to personal wisdom and an intimate understanding of one’s own sphere of control. It’s a viewpoint that challenges us to look introspectively at our own suffering, the role of fate, and the value we ascribe to life’s experiences.

Ancient Greek Views on Suicide

In sharp contrast to the Stoics’ measured approach, the broader tapestry of ancient Greek thought often painted suicide as a defiance of divine will. Many Greeks believed that life was a gift from the Gods, and thus, humans were, in a sense, the property of these celestial beings. To take one’s own life was to reject this divine gift, an act of rebellion that could potentially incur the wrath of the Gods.

This perspective is deeply rooted in mythological narratives and the Greek understanding of hubris—the dangerous overstepping of one’s place in the order of things, often against the divine. By usurping the role of the Gods in determining life and death, an individual committing suicide could be seen as committing the ultimate act of hubris. Such views can be traced back to around 500 BC, reflecting a time when religious and superstitious beliefs heavily influenced societal norms and ethical judgments.

The tension between these views—Stoic rationality and ancient Greek piety—offers a glimpse into the rich philosophical tapestry that has grappled with the concept of suicide through the ages. From the Stoic embrace of personal wisdom to the Greek reverence for divine will, these perspectives echo the enduring quest to understand the human condition and the sovereignty we hold over our own lives.

In the following sections, we’ll continue to explore the philosophical landscape surrounding life’s most profound questions and the moral implications of choosing to step away from them.

Philosophical Perspectives on Life, Suffering, and Persistence

The tapestry of human existence is woven with threads of joy, sorrow, triumph, and tribulation. Philosophy, in its quest to unravel the complexities of life, has long grappled with the shadows of suffering and the light of resilience. Consider the profound insight, “To live is to suffer, to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering.” This notion captures the essence of our journey through the labyrinth of life, where every hardship bears the potential to be alchemized into wisdom.

Life’s labyrinth is not a sprint but a marathon, and herein lies the virtue of persistence. The adage, “It does not matter how slowly you go as long as you do not stop,” serves as a beacon for those navigating through the fog of despair. It reminds us that the pace of progress is secondary to the relentless pursuit of moving forward, step by step, towards the dawn of understanding and acceptance.

Each individual’s odyssey is punctuated by moments of introspection and confrontation with life’s fundamental questions. In the stillness of such moments, philosophical musings emerge, such as “Know thy self, know thy enemy. A thousand battles, a thousand victories.” This wisdom exhorts us to delve deep into the self, to understand our inner world as intimately as we seek to comprehend the world without. It is in this understanding that one may find the keys to enduring life’s myriad challenges.

In the context of the stoic endurance, the insight “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing,” attributed to Socrates, underscores our perpetual dance with uncertainty. It is the humble acknowledgment of our limitations that often ignites the flame of curiosity and the relentless search for meaning amidst existential suffering.

As we ponder the philosophical dimensions of existence, it is crucial to recognize that the contemplation of life’s worth is a recurring theme across various schools of thought. The Stoics, for instance, would weigh the notion of suicide with a sagacious balance, measuring it against the virtues of wisdom and self-control. And yet, the ancient Greeks would perceive such an act through a prism of defiance against divine providence, a rebellion against the deities that weave the fates of men.

In this intricate interplay of light and shadow, life and death, philosophy offers not just a reflection but also a compass. It guides us through the tumultuous seas of suffering, encouraging the cultivation of resilience and a search for deeper meaning. As we sail forth, it is this philosophical wisdom that whispers to us in the silent hours, urging us to persist, to learn, and to grow, regardless of the tempests that may come our way.

Philosophy teaches us that the night is darkest just before the dawn, and it is the courage to continue that gets through many a dark night. For in the pursuit of life’s enigmatic purpose, it is not merely the will to survive that shapes our destiny, but the unyielding spirit to thrive, finding meaning in each step of our mortal voyage.

Philosophical Quotes on Knowledge and Quality

Embarking on a quest for wisdom, philosophy teaches us to embrace humility in the face of the vast expanse of the unknown. It reminds us that the journey towards knowledge is infinite, and true wisdom lies in the recognition of our own limits. The ancient adage, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing,” attributed to Socrates, encapsulates this profound understanding. It suggests that the more we learn, the more we realize how much there is yet to discover—a humbling thought that fuels our thirst for lifelong learning.

In parallel, philosophy extols the virtue of quality, not as a singular act but as a persistent practice. Aristotle’s timeless insight, “Quality is not an act, it is a habit,” speaks to the core of excellence. It is through the repeated effort and unwavering commitment to refinement that quality emerges, transforming actions into enduring standards. This perspective inspires individuals to cultivate excellence in all facets of life, nurturing habits that lead to the betterment of the self and society.

Philosophy and Death

Philosophy’s contemplation of death is as varied and deep as its musings on life. It challenges us to confront mortality with courage and to question what it means to truly live. Marcus Aurelius, a Stoic philosopher-emperor, urged us to reflect on life’s brevity with the words, “It is not death that a man should fear, but he should fear never beginning to live.” This poignant reminder encourages us to seize life’s moments, to live authentically, and to eschew the stagnation that comes from fear.

Furthermore, the idea that “Death is nothing, but to live defeated and inglorious is to die daily,” attributed to Seneca, another Stoic thinker, invites us to consider the daily choices we make. It suggests that a life lived without purpose or victory over personal challenges is akin to a perpetual death, emphasizing the significance of overcoming obstacles and forging a life of meaning.

These philosophical musings act as a beacon, guiding us through the ebbs and flows of existence. They urge us to contemplate the fabric of life, the essence of knowledge, and the pursuit of quality, while simultaneously reminding us of the inevitability of death and the imperative to live fully in the time we have.

Hope Theory and Suicide

In the labyrinthine journey of human existence, hope acts as a guiding light, steering individuals away from the shadows of despair. The hope theory of suicide, a concept deeply rooted in psychological research, posits that hope—or the absence of it—can significantly influence one’s vulnerability to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This theory examines the intricate relationship between an individual’s past and their capacity to envision a future worth striving for.

Central to this theory is the understanding that hope is not merely a fleeting feeling but a trait that can be cultivated—or stifled—by life’s experiences. According to esteemed psychologist Charles R. Snyder, who pioneered the hope theory, people who have endured childhood adversity often find themselves at a crossroads. The turbulent waters of their early experiences may have swept away the building blocks of hope: agency and pathways thinking. Agency imbues one with the belief in their ability to shape their future, while pathways thinking equips them with the strategies to navigate obstacles.

Without these vital components, an individual’s trait hope remains stunted, much like a sapling deprived of sunlight. This lack of hope can cast a long shadow over their adult life, leaving them susceptible to the siren call of suicidal ideation. Snyder’s research, crystallized in 1994, illuminates how this deficit of hope can act as a silent assailant, increasing the risk of suicide, particularly when life’s storms rage fiercely.

It’s essential to understand that hope is not a static entity; it is dynamic and responsive to the environment. As such, the hope theory offers not only insight into the mechanisms of suicidal risk but also a blueprint for intervention. By fostering agency and pathways thinking, even those who have wandered through the darkest valleys of their past may find a way back to hope’s embrace. They can learn to rebuild the inner architecture of hope—one thought, one action, one dream at a time.

Through this lens, hope becomes more than just an abstract concept—it is a tangible lifeline that can be strengthened and extended to those teetering on the edge of oblivion. It beckons us to understand that the past need not dictate the future, and that every individual has the potential to rekindle the flames of hope within their hearts.

As we continue to explore the philosophical dimensions of suicide, it is crucial to remember that theories like Snyder’s serve as a reminder of the profound power hope holds in our lives. In the following sections, we shall delve deeper into the sociological aspects of suicide, specifically the four types of suicide identified by Emile Durkheim, which offer further predictors for understanding this complex phenomenon.

The Four Types of Suicide According to Durkheim

The study of suicide, a subject often shrouded in taboo and sorrow, was profoundly explored by Emile Durkheim, a pioneering French sociologist. In his groundbreaking work, he dissected the act of suicide into four distinct types, each illuminating the intricate interplay between the individual and societal forces. These classifications are not mere academic constructs but are essential keys to understanding the societal dimensions that contribute to the phenomenon of suicide.

Anomic Suicide

First, there is Anomic Suicide, which occurs in a state of normlessness where societal norms are disrupted due to significant societal changes like economic depression or wealth. Individuals lose their sense of belonging and purpose, finding themselves adrift in a society that no longer provides stable structures to guide them. In the modern context, this might resonate with the feelings of disorientation and purposelessness that emerge during periods of rapid social or economic upheaval.

Fatalistic Suicide

Opposite to an anomic state is Fatalistic Suicide, born out of excessive regulation and oppressive discipline that suffocate the individual. This type of suicide might be seen in environments where one’s future is relentlessly predetermined, such as in extremely authoritarian societies or institutions, leaving individuals with feelings akin to being trapped in an inescapable, bleak destiny.

Egoistic Suicide

Thirdly, Egoistic Suicide arises from a sense of extreme detachment from society, where individuals feel isolated or not integrated into the social fabric. This detachment often results from weakened bonds and a lack of communal support, which can be exemplified by the loneliness that might be experienced in our increasingly individualistic world.

Altruistic Suicide

Finally, Altruistic Suicide is characterized by a too strong integration into society, where individuals sacrifice their lives for what they perceive as the greater good. This can be observed in acts of self-sacrifice for one’s country or community, or in historical practices like ritualistic suicide in traditional societies.

Understanding these types of suicide according to Durkheim not only casts light on the societal underpinnings of this tragic act but also emphasizes the importance of the balance between individual agency and societal structures. While an individual’s decision to commit suicide is deeply personal, Durkheim’s typology suggests that the fabric of society plays a critical role in either nurturing hope or pushing individuals towards despair. His work aligns with the hope theory of suicide, suggesting that where society fails to cultivate hope, individuals may become more vulnerable to suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

In conclusion, the philosophical perspective on suicide is indeed multifaceted, and Durkheim’s typology provides a vital lens through which we can understand the societal factors at play. It encourages us to reflect not only on the moral and intellectual dimensions but also on our collective responsibility to create a society that bolsters the hope and well-being of its members.

FAQ

Q: What is a philosophical quote about suicide?

A: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.”

Q: What is the suicide philosophy quote?

A: “When a man destroys his existence as an individual, he is not by any means destroying his will to live. On the contrary, he would like to live if he could do so with satisfaction to himself; if he could assert to provide good services to others.”

Q: What are some philosophical quotes about death?

A: “Death is about things which are beyond the power or our will. It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters. First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do.”

Q: What is the fundamental question of philosophy regarding suicide?

A: “There is only one really serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is worth living is to answer the question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards.”

Leave a Reply